This page talks about:

- -- the reasons for the "white line strategy" for horses that have

just had the shoes pulled;

-- differences in strategy, comparing the wild-horse and Strasser trims.

(For discussion of the wild-horse trim vs. the typical farrier trim, see Hoof Shape page and a short section on the Home page.)

There are two things that commonly make a horse sore after you pull the shoes:

1) If you thin any area of the sole (other than scraping off chalky or flaky material with a hoofpick) most horses will be sore until the sole grows back to its full thickness. The sole grows about 1/8 inch (3 mm) per month and is about 3/8 inch (1 cm) thick. Thus, if you thin part of the sole 1/8 inch (3 mm.), you can expect soreness during the month while that 1/8 inch is growing back.

You can avoid this type of soreness by not thinning the sole. If you use a farrier, do not let him thin the toe callus; they do this habitually, in preparing the hoof for a shoe.

2) Shod horses have damage to the white line (laminae), due to reduced circulation inside the hoof. Damaged white line is stretchy, allowing the coffin bone to press down onto the sole corium; the corium stays chronically inflamed, and the horse goes sore on gravel, rocks, or pavement. (See drawings on Transition page.)

You can substantially reduce this shoe-caused type of soreness, and shorten the Transition period, by trimming as shown below.

How this strategy came about

When Pete Ramey heard about going barefoot, several years ago, he pulled all the shoes on the 30 livery horses that he cared for. Motivated to keep the horses in work to make a living, he did lots of trial-and-error to find out how to go barefoot without making them sore.

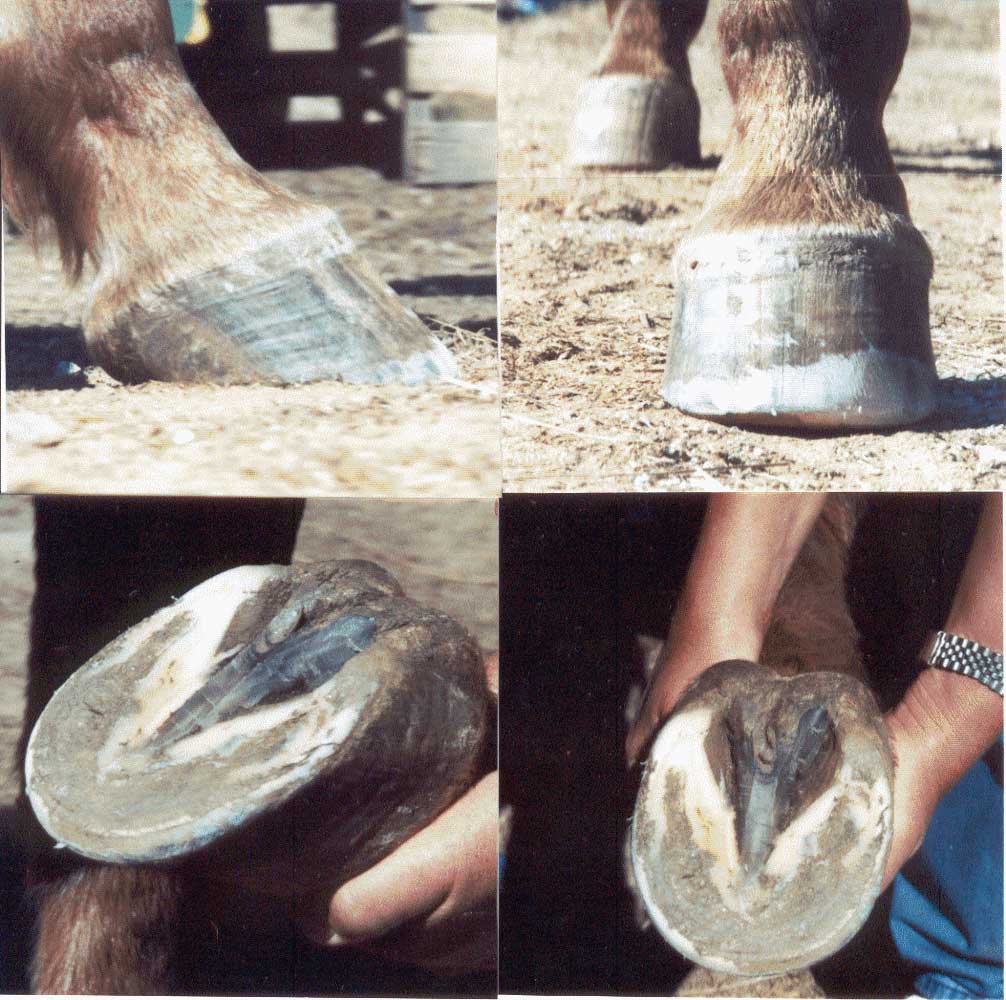

Here are the feet of some of those trail horses. They were trimmed

3 to 4 weeks previously, so the mustang roll is somewhat worn down. Pete's

trim has changed somewhat since I took these photos in about 2002.

|

Jim, age 37 (!) Pete touched up his trim; you can see the lighter coloring in some areas. I rode Jim on a trail ride; he gaily kept up with the others, galloping easily over rough and gravelly ground. |

|

Marlon Wayne, 4-year-old draft horse, never shod. Notice how wide his frog and bulbs are, and how much concavity there is in the sole. His feet will grow wider for another couple of years as his weight fills out. |

A Transition Strategy for Minimal Soreness

Transition begins when you pull the shoes, and lasts until the horse can walk on gravel or rocks without being sore, and the sole regains its own true concavity.

NOTE: if you trim in a way that allows the white line to keep stretching out (and the wall to flare), the horse can stay permanently in a "transitional" condition.

A trim strategy puts a priority on certain parts of the trim, depending on your views of what is important for healing.

Pete Ramey's strategy is to get the horse comfortable and back to work quickly. His priority is to tighten up the white line, which reduces laminar pain from the beginning and prevents ongoing, painful flaring. He trims in a certain way to accomplish that. I show this trim on the "Do Trim" page.

For comparison: Dr. Strasser's strategy is to increase circulation inside the hoof. Her priority is to maximize hoof mechanism, and she trims in a certain way to accomplish that. (See "Comparing trims" below.)

Many trimmers have found that the "hoof mechanism" strategy can interfere with white line recovery. When you allow a barefoot hoof to continue for several months with a separated white line, the result can be a loss of sole concavity, and eventually a mechanical-founder situation.

Dr. Strasser states that you can modify her "basic" trim to fit the needs of the individual hoof and how hard the ground is, that the horse is living on. It is OK to modify the Strasser trim in the ways noted on this page, if you decide to give priority to getting the white line tightened up.

Some background

The "white line" refers to the laminae, which suspend the coffin

bone inside the hoof capsule. Laminae look like the "gills" on the underside

of a mushroom. There is a set on the surface of the coffin bone, and another

set on the inside of the hoof wall. The two sides interlock, sort of like

Velcro, and make an amazingly strong connection -- it takes two people

to peel the hoof wall away from the coffin bone of a cadaver hoof.

|

|

| Here is a view looking into a hoof capsule, showing the laminae on the inside surface of the hoof wall. You can see where they turn the corner and continue onto the bars. The black spots on the coronet are pigment; it was a striped hoof. |

|

| Here is a hoof sliced in half, showing how the coffin bone fits into the hoof capsule. (These feet spent several months buried in the garden; the laminae on the coffin bone are gone.) |

|

| Here is a hoof with white line separation. You can see the space between the wall and the sole along both quarters, and the accumulated dirt in the white line on the left side. You can also see that the overgrown hoof wall is flared; the outline of the wall doesn't match the curve of the sole. "Flare" and "stretched white line" are the same thing. |

When the white line is stretched, the force of the ground pulls the hoof wall away from the coffin bone. (See drawing of "ground pushing up" on Transition page.) This feels similar to pulling your fingernail off; the pink stripey stuff that holds your fingernail on is the same kind of tissue as the horse's white line. The white line cannot re-attach itself once it is separated. A new connection must grow down from the coronet (hairline). This usually takes about a year, if you use the white line strategy consistently.

For the horse's comfort, the top priority is to remove this stress on the white line, so that it is not painful and further stretching is prevented. Although the horse will be "walking on the sole" for a while, this is observably much less painful for them than walking on a stretched white line. We can use protective pads for 2 or 3 days in the beginning, if needed; after that, owners generally report that their horse is "running and bucking in the pasture."

When the white line connection is finally tight, three notable things happen:

- 1) Rather suddenly, from one trim to the next, the sole will go

concave as the coffin bone is raised up inside the hoof capsule.

2) With feet that finally feel good, the horse is more lively.

3) The horse is able to walk on gravel, rocks, pavement, or frozen ground without pain.

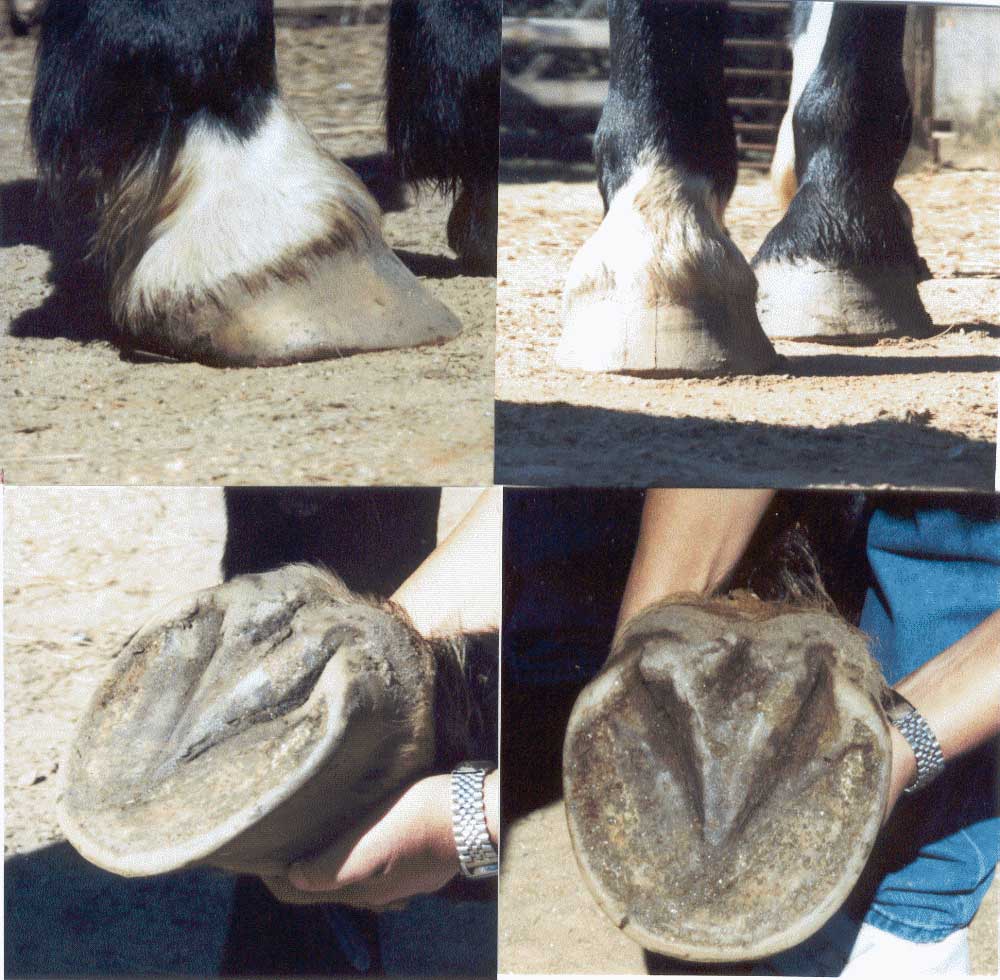

|

Here is the sole of a front foot that has always been barefoot, showing true concavity. I watched this Icelandic horse walk across sharp gravel in the driveway like it was grass. Note the white "water line." The hoof was wearing evenly, and hardly needed to be trimmed. |

The White Line Strategy

|

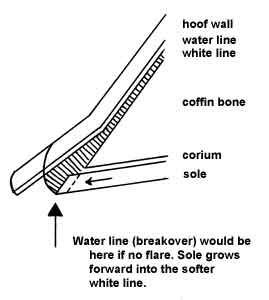

To rehabilitate the flare, mustang roll to the edge of the grown-forward

sole. Renew weekly until the white line is no longer stretched.

When the white line has tightened up, use the normal mustang roll, which ends at the water line. |

Turnout

All transition strategies agree on this point:

24-hour turnout is important to rapid rehabilitation of the de-shod hoof.

The hoof needs a huge and constant supply of fresh blood. When a horse stands in a stall, the hooves quickly become congested. Metabolic wastes build up inside the feet. Areas that are healing are deprived of oxygen and nutrients. I have seen feet that were doing well during daytime turnout, become sore overnight in a stall.

Currently it's difficult for many of us to arrange 24-hour turnout for our horses. Begin with the best you can do, and keep working toward longer turnout / shorter stall time. As more people come to understand the importance of movement, we will change the standards of boarding conditions.

Comparing trims

Here are the differences and similarities between Dr. Strasser's "Basic Trim" as I learned it in 2001, and the "wild-horse" trim; with the reasons as I understand them.

Dr. Strasser originally designed her trim for the rehabilitation of extremely deformed, lame hooves that other veterinarians had given up on -- sometimes after years of "conventional" treatment. Her strategy is to remove most of the deformed material and quickly give the horse a basic hoof that will circulate blood (hoof mechanism), so that he has the means to heal his own hoof.

She kept the horses on rubber mats for several months until the hooves recovered enough to go on soft ground comfortably. If you don't have a large rubber-matted area, you should modify the "Basic Trim" toward a much less radical trim. For hooves that are not extremely deformed, Dr. Strasser's "Basic Trim" can be unnecessarily severe.

The "wild horse" trim was designed to return shod horses to a barefoot condition, shaping the hooves like those that free-roaming horses produce through constant growth-and-wear. Since the hooves are already sound, or nearly so, the shape can be changed gradually towards the ideal, while the horse continues to live on its usual terrain.

In order to quickly increase circulation, the Strasser trim does several things to increase or even exaggerate hoof mechanism:

1) Strasser trim: Trim the sole to mimic the concavity of a sound hoof. The reason is that the thinner sole spreads easily, which allows the bottom edge of the hoof wall to flex wider during weightbearing, giving increased hoof mechanism.

Wild horse trim: Leave the sole at its full thickness. The sole is considered to be an important structure. It helps to hold the hoof together, helps prevent white line separation, and protects the interior of the hoof from the ground. In a sound or nearly-sound hoof, there is already sufficient hoof mechanism. Leaving the sole at its full thickness avoids soreness and abscessing. Concavity will occur naturally when the white line has fully recovered from the damage caused by horseshoes.

2) Strasser trim: Shorten the bars to end halfway along the frog, with a bar height of 1 cm halfway along the bars; then slope the sole in the seat-of-corn to meet the shortened bar. This is done to help de-contract contracted heels, which increases hoof mechanism.

Wild horse trim: Trim the bars to the level of the sole or slightly longer, though not in contact with the ground. The connection between the bars and the sole is considered an important part of the heel structure; it helps to hold the hoof together under the forces of weightbearing. De-contraction is accomplished, instead, using the toe rocker (see Trim page) or mustang roll to eliminate forward toe leverage on the heels.

3) Strasser trim: Make notches or "opening cuts" if contracted heels are curved inside a line from the point-of-frog to the outside of the bulbs. The reason is to encourage contracted heels to de-contract, which increases hoof mechanism.

Wild horse trim: Omit "opening cuts." Depending on climate and terrain, they can actually increase heel contraction (heels leaning inwards), or increase white line separation (heels leaning outwards). Instead, de-contraction is accomplished gradually by rockering or mustang-rolling the toe to eliminate forward toe leverage on the heels.

4) Strasser trim: Trim the heels to a 3.5 cm height (vertical from the back corner of the lateral cartilages). The reason is to quickly place the coffin bone in a ground-parallel position, which increases hoof mechanism. If, when shortening the heel to this measurement, you get to blood in the seat-of-corn, wait till the sole recedes before you shorten the heels more.

Wild horse trim: Trim the heels only to the outside edge of the sole in the seat-of-corn. The reason is to avoid thinning the sole, which can sore the horse. If the heels are long when trimmed to the sole, the sole in the seat-of-corn will recede over time (as the bone re-shapes itself), allowing gradual shortening of the heels.

5) Strasser trim: Trim the hoof to a 30-degree hairline while the hoof is on the ground, with front toes at about 45 degrees and hind toes at about 55 degrees. The reason is to quickly place the coffin bone in a ground-parallel position, which gives the hoof capsule the most efficient shape for hoof mechanism.

Wild horse trim: Trim the hoof wall to the edge of the sole. Often, trying to get an exact 30 degree hairline makes you shorten either the toe or the heel too much, thinning the sole and soring the horse. The hairline angle will change gradually as the hoof returns to its own inherent shape.

There is one more difference between the two trims, not related to hoof mechanism:

Strasser trim: Finish the hoof wall with a flat bottom. The reason is that the long, flat toe will encourage the pastern to a lower angle, in hooves that have had the heels too long. A flare, or a toe "long out in front," can be backed with a vertical cut, to where the outside of the wall (if not flared) would meet the ground.

Wild horse trim: Finish the hoof with a rounded bevel ("mustang roll") to the water line (inside layer of hoof wall). The reason is to give the hoof a fast breakover; reduce flaring (white line separation); and remove the lever force of a long toe, which contracts the heels. A flare, or a toe "long out in front," can be rockered and then rounded as far as the edge of the sole, reducing the additional lever effect of the flare.

Dr. Strasser sometimes uses a "modified" trim on sound horses. This trim is quite similar to the wild horse trim and omits these radical steps (except for the long breakover). I believe she would serve the population of sound horses better if she would teach her "modified" trim at the 3-day introductory seminars, where many of the students are beginners, and save her "basic," more radical trim for students in the professional course.