Hoof words

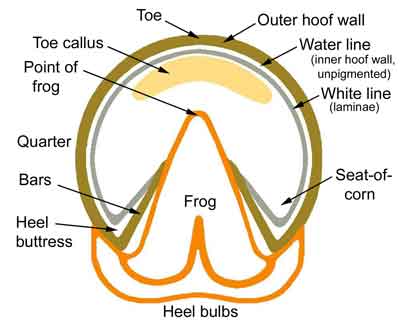

Here is the bottom of a hoof, with the names of the parts:

A hoof trimmed to the wild-horse shape is different from what we are used to seeing all around us.

Here are photos from wild horses that lived and died on dry, rocky, mountainous terrain. The heel bulbs have been mostly chewed off by scavengers, but otherwise the hooves are in excellent shape.

(The word "mustang" is a U.S. word meaning a feral horse, living generally in open country on plains or mountainsides -- "brumbie" in Australia. "Mustang roll" refers to the rounded bevel around the bottom of their hoof wall.)

A front foot:

|

-- hoof length is very short (about 3 inches or 7.5 cm.) because the extremely healthy "white line" places the coffin (pedal) bone high inside the hoof capsule. Bottom edge of wall is worn to a rounded bevel (mustang roll). Domestic hooves will not be this short. |

|

-- tight "white line" (weathering makes it look dark) with no

flared

wall

-- white line of the bars is visible ("bars" are the part of the hoof wall that turns inward beside the frog) -- heel looks contracted because the frog has dried out on this cadaver |

|

-- longest part of the foot is the "water line," the inner,

unpigmented layer

of hoof wall (lightest layer in photo); outer pigmented layer is not weight-bearing and functions

mainly as protection

from sharp rocks

-- front foot has shallow concavity -- about 1/4 inch (6 mm) if you lay a straight edge across the foot at the point of frog. Front foot is a "landing foot" with a shallow coffin bone that will not break under the horse's sudden weight after jumping |

|

-- strong, callused heels and arched quarters

-- this toe, from rough terrain, is worn off to nearly halfway up the wall, in addition to mustang roll at the bottom; a domestic toe would be straight |

|

-- tight "white line" (weathering makes it look dark) |

|

-- hind foot has deeper concavity than front foot, like the deep treads on

the rear wheel of a

tractor, for traction

-- the unpigmented layer is longest, and breakover occurs there |

Another hind foot.

|

-- toe wall is worn well up the toe, in addition to mustang roll

-- mustang roll allows early breakover |

|

-- toe length is much shorter than hoof width, due to very healthy, tight

white line

-- mustang roll continues around the sides of the hoof |

|

-- one bulb on this one is not chewed off; you can see the more oval shape of the complete hind foot |

|

-- deep concavity of hind foot, with frog worn and compressed by rocky terrain |

Domestic hooves will not be as short as these. Most of our horses don't travel enough daily miles on hard ground, to have a totally healthy, tight white line. The white line is weakened and stretchy, therefore the wall and coronet migrate upward toward the pastern. In domestic horses we can expect toe lengths of about 3 1/4 to 3 3/4 inches (8 to 9.5 cm) measured from the hairline along the toe to the ground.

DO NOT try to trim a domestic hoof as short as these mustang feet. You will have to thin the sole to do it, and this will make your horse very sore.

The hoof is a flexible structure which responds directly to the mechanical forces upon it, from the leg above and from the ground beneath. Watch what happens in a hoof from one trim to the next. You'll find a little flare starting over here; one heel wearing more than the other; the toe getting too short or too long. Then you have to think about what made it do this, and use today's trim to encourage the hoof to return towards its ideal shape.

I highly recommend that you ask one of your friends to be a "trimming buddy." When I was learning, I met for several years with friends to go over their horses' feet, or mine. We looked at them carefully and thought together about what was happening in each foot. Their input, questions, and support made it possible for me to keep learning and to keep going through discouragements.

Coffin bone (pedal bone)

Here is a reasonably healthy coffin bone from a front foot -- top, side, and bottom:

The hoof is built around the coffin bone. The hoof wall and sole are attached to its surfaces. The toe angle of a well-attached hoof wall must match the angle of the coffin bone; if it does not, there is white line (laminar) separation.

Surrounding the bone is a thin layer of tissue called the corium which has an extremely dense blood supply. The hoof is a high-priority organ for the horse's survival. All tissue-building, maintentance, and healing in the foot depend on the constant supply of nutrients brought to the corium by the bloodstream.

The sole is made in part by the corium on the bottom of the coffin bone, and in part by the white line (laminar layer) of the bars.

On the outer / upper surface of the bone, the corium builds a set of soft, fine "leaves" (lamellae) which match a set of hard "leaves" (laminae) on the inside surface of the hoof wall. The two sets of "leaves" interlock like a sort of living Velcro, holding the wall and bone together. They are nearly impossible to pull apart. Laminar tissue is the same as the stripey tissue that holds your fingernail onto your finger.

NOTE that the wall does not grow vertically down from the coronet. It follows the slope of the coffin bone. The entire hoof wall, including the heels, grows forward at this slope. The hoof is a slanted cone shape, narrower at the top and wider at the bottom.

The hoof wall and laminar side of the white line are mostly made at the coronet (and some locally at the laminae), in the same way that our fingernail is made at the quick. The hoof wall grows down the outside surface of the coffin bone, strongly attached by the laminae. It takes almost a year for the hoof wall to grow out completely at the toe, where it's longest.

What "GROUND-PARALLEL" means. The sharp, curved bottom edge of the coffin bone makes an arc (like a new moon). For correct alignment of the leg bones, this curved edge should sit nearly level on the ground. What you see on an x-ray is not the bottom edge (which is too thin to show up well) but a cross-section through the body of the bone, which is concave so that it slopes upward. It's very hard to see the bottom edge of the coffin bone on an x-ray, and therefore to know whether your horse's coffin bone is ground-parallel. Instead, we can determine ground-parallel by using the sole (which matches the bottom of the coffin bone) as a guide to trimming the hoof.

The Frog

The frog is a crucial structure of the hoof. It grows from the frog corium, which has a dense blood supply. Its job is to absorb concussion when the foot strikes the ground, and to spread the heels slightly apart, assisting circulation of blood inside the foot. A correctly trimmed hoof with no infection in the frog should strike the ground heel-first, with the frog in ground contact and taking the impact of the horse's weight.

In a healthy, well-trimmed foot that has never been shod, the frog is a wide, plump structure similar to the biggest pad of a dog's or cat's paw. It is made to take impact and absorb concussion. Its health is maintained by the fact that it is in contact with the ground between the heel buttresses, and receives concussion at every step.

The frog should share the horse's weight with the sole, bars, heels, and water line (the white inner layer of hoof wall). Weight carried by the outer wall (as in a shod horse) is called "peripheral loading" and over time will damage the laminar tissue (white line) that holds the wall tightly onto the coffin (pedal) bone. Peripheral loading is one of the mechanical forces that causes or allows flaring of the wall away from the bone, leading to mechanical founder.

The frogs of shod horses are held 1/2 inch (1 cm) above the ground by the thickness of the horseshoe. They do not receive the concussion that they require, they become narrow and unhealthy, and they are often infected with yeasts ("fungus") and bacteria ("thrush"). The narrowed frog is unable to hold the heels apart, thus the heels contract; and the mechanical forces on the contracted heels further squeeze the frog into a narrower shape.

When we pull the shoes off a horse, the frog will be able to become plump and healthy again. Generally it is necessary to treat for infection (see More Topics page) so that the frog is not painful and the horse is willing to put weight on it.

If the heels are long, you can shorten them -- gradually over several trims -- until they are near the level of where the frog and heel buttress meet at the back of the foot. Often it is necessary to leave the heels 1/8 to 3/8 inch (3 to 10 mm) long to protect the diseased frog (and the weakened digital cushion above it) for several months while they become stronger.

The front feet will be unable to land heel-first until the heel is near the level of the frog, and the toe (if flared forward) is backed-up to the correct breakover position (see Breakover page). Hind feet land heel-first more easily, due to the zig-zag arrangement of the hind leg joints.

The Sole

The sole protects the coffin (pedal) bone from damage by rocks and hard ground. It is made by a spongy, blood-filled layer of tissue called the sole corium on the bottom of the coffin bone. The sole grows to an even thickness across the entire bottom of the coffin bone -- 1/2 inch (1 cm) in most domestic horses, and up to twice that thickness in wild horses living on rocky terrain. The outer surface of the sole becomes hardened like a callus, especially around the toe under the sharp edge of the coffin bone.

The horse's foot needs the full thickness of sole, across the entire bottom of the coffin bone, for protection. If we trim the sole, the horse loses both some thickness and the hard, calloused surface. The foot will be painful, and is vulnerable to bruising on rocks and fracture of the coffin bone.

Because the sole is an even thickness over the entire bottom of the coffin bone, we can use it as an accurate landmark for trimming the wall. When the wall is trimmed level with the sole -- the water line being no more than 1/16 inch (1 or 2 mm) longer than the nearby sole -- this puts the coffin bone in its correct position in relation to the ground (ground parallel). The sole is a more reliable guage for correct hoof shape than toe angle, because the toe wall may be flared away from the bone and therefore may give innaccurate information about the position of the coffin bone.

"Wild horse" shape vs. typical long-heeled style

Barefoot works best when the horse's foot is trimmed to a fairly short-heeled shape. The drawings below of a short- and long-heeled shape (not accurate in details) show what happens to the coffin bone when the heels are long.

Click

here to go to an

excellent article in Professional Farrier Magazine, that explains the problems with the "box

foot trim."

-- coffin bone is "ground-parallel" (level) -- pastern is sloped for good shock absorption |

"Box foot" trim used by many farriers -- coffin bone is not "ground-parallel" -- pastern is upright, loss of shock absorption |

Bottom view of a "triangle foot" -- frog and heels are wide -- bulbs are wide apart -- heels meet the corners of the frog -- bars are straight, making a strong heel structure |

Bottom view of a "box foot" -- frog and heels are contracted -- bulbs and frog are creased together -- heels are forward from the corners of the frog -- bars are squeezed into a curve |

|

|

On the left, with a ground-parallel coffin bone, the pastern makes

a long, shock-absorbing curve.

On the right, with a long heel, the coffin bone is not ground-parallel. The steeper pastern angle absorbs less shock, the force of the leg comes at an incorrect angle into the coffin bone, and there is a lot of toe pressure on the sole. This hoof in fact had long heels. You can see rough calcifications on the palmar processes (back corners) and some sidebone developing (swelling above the heel). |

|

Here are coffin bones from (right) a healthy hoof and (left) a hoof

that had shoes and long heels for many years.

The coffin bone on the left has a toe notch. The bone "eroded" at the tip (removed bone where it pressed into the sole). A toe clip on the shoe can also make a toe notch. You can also see how the palmar processes (back corners of the coffin bone) have been squeezed (contracted) into a narrower, straighter shape than in the healthy bone. |

What are "underslung heels"?

|

A well-trimmed, sound hoof, showing the direction of wall growth.

The entire hoof wall grows from the coronet at the same slope as the coffin bone. Everything grows down-and-forward, including the heels. No part of the hoof grows vertical (unless it is trimmed "box foot" style with a long heel and short toe). I have put lines following the wall growth at toe, quarter, and heel. Pink arrow shows a slight groove in the tubules ("hair" material that the wall is made of) which has the same slope as my lines. If we let this foot get overgrown, the heel will be longer, and will also be forward of where it is now. That will not be an "underslung" heel. To be "underslung," the heel must also be curled in under the foot, as a contracted heel is curled in. |

|

|

| A very overgrown hoof that has always been barefoot, showing how

the heels normally grow forward and outwards as they grow longer. Although

these heels are forward, they are not contracted, and therefore they are not "underslung."

When the horse weights his foot, the heels spread apart. After a trim, this will be an excellent foot; note the wide, healthy frog.

|

An "underslung" or "under-run" heel. The shoe

prevented the hoof

from getting wider as it grew; instead it curled under, making a long cylinder

shape. The heel and frog are squeezed very narrow.

When the horse steps on this foot, the heels are forced inwards. Rehabilitation may be difficult -- it's hard to get the heels spreading apart when they are this squeezed. If you force it with over-eager trimming, it's easy to cause white line separation from the contracted coffin bone. The heels need to be shortened to the edge of the sole, after scraping out a lot of chalky material in the seat of corn. The toe will need to be backed up -- it's been pulled way out in front and is probably flared all the way to the coronet. This horse will need many months of long walks on medium-firm ground (not sand, not soft arena, not pavement) to encourage re-shaping of the hooves. |

"Inside the vertical"

Front hoof (left and center) of a horse that was raised in Florida, where the ground is soft and sandy. I suspect that, as a foal, he spent a lot of time standing in soft bedding. His feet did not receive enough concussion to spread out. (See Photo Gallery 2, #10 and #15)

The hoof wall is what we call "inside the vertical"-- it is narrower at the bottom than at the top. This shape cannot expand during weightbearing; thus it does not provide much circulation in the hoof and grows poorly. It is difficult to rehabilitate.

The dirty area in front of the point-of-frog is a hollow in the sole. Because the heels are long, the coffin bone presses down on the sole corium in that area. Sole growth was slowed and the sole is thin there.

On the right, a normal hoof showing the cone shape which spreads on weightbearing, providing circulation inside the foot.

| A flare is an outward curve at the bottom of the hoof wall,

like the bell of a trumpet. The hoof wall should be a straight line from

the hairline to the ground, all the way around the foot.

These feet are flared because they are overdue for a trim. More frequent trimming will get rid of these flares quickly; note the upper part of both feet has a strong white line connection. We often find a "straight flare" at the toe of shod horses. It's harder to recognize as a flare because it looks straight from coronet to the ground, but it is a flare because the white line inside is stretched away from the coffin bone. |

|

The hind coffin bone is usually a few degrees steeper than the front, so the toes on the hind feet are generally steeper than the front toes.

If the hind toes are shallow and have gone "long-out-in-front," suspect pain in the front feet. The horse puts the hind feet forward, underneath himself, to take weight off the front feet, and the heels wear faster.

Horses that do a lot of collected work can also get long-in-front toes in the hind feet. Keep the toes backed up and be sure the horse gets plenty of non-collected exercise for more balanced wear.

Getting clues from posture and movement

Here are some things to see about the way a horse moves and stands. Watching your horse walk is a good way to check your work before and after you trim.

If you walk behind the horse and see a hind leg plant itself firmly

on the ground with no sideways wobble, that hind foot is balanced. If the hock

wobbles, the hoof is longer on one side. (For your encouragement, I

have gotten all the wobble out of my horses' hind legs.) Wobble to the

outside means inside of hoof is long; wobble to the inside means outside

of hoof is long.

|

If the front or hind feet are close together (base-narrow), you

will find the insides of those feet long. If the front or hind feet are

spread apart (base-wide), you will find the outsides long.

This Icelandic was base-wide. I trimmed a tiny amount, about 1/16 inch (1.5mm) on the outsides and he was able to stand much better. You don't want to trim into the sole, only to look for where the wall is a little long. This fellow needs lots of lateral work (such as Parelli "sideways game") to strengthen and widen his chest. |

To see which side is long, look at the hoof from directly in front of where the knee faces; the tubules (lines in the hoof wall) will not be vertical. When you look at the bottom of the foot, one side will be longer than the other.

If these landmarks (sole view and tubules) don't agree, then the coffin bone may have dropped on one side (stretched white line), or possibly eroded to a crooked shape -- one of the coffin bones in my collection slants about 5 degrees from level. Gene Ovnicek recommends to trim for a heel-first landing; then the hoof will re-shape itself easily.

A front foot that "wings" or "paddles" is long on the outside. My gelding used to paddle at the trot, but it stopped when I got his feet balanced.

A horse with unbalanced feet will have trouble squaring up, and usually puts one leg ahead of the other. A foot placed behind its correct position may have painful heels; a foot placed in front of its correct position may have pain at the toe. Or, a foot may compensate for pain in the diagonal foot. A horse with comfortable feet stands squared-up with the cannon bones vertical.

Unevenness in a horse's movement may indicate the spine needs chiropractic adjustment. Generally, vertebrae get out-of-line due to consistently uneven posture from unbalanced feet. The situation can also work in reverse -- a vertebra popped out of line in a fall can result in uneven hoof wear.