On this page:

- -- Fungus infection in hooves

-- "Navicular syndrome"

-- Healthy hooves for foals

-- Suggestions for trimming foals

-- Colts starting in work

-- Hoof damage from carrying rider's weight?

-- GMO's in horse feeds

-- Trimming donkeys and mules

-- "Club foot"

FUNGUS INFECTION IN THE FROG

In wet climates or the wet season, we see quite a lot of fungus or "thrush" infections in the frogs of domestic horses. It seems to be similar to "athlete's foot" (tinea pedis) and yeast infection (Candida) in humans. Horses living in dry climates can have it too.

Fungus is what people in wet climates call, "My horse's frogs seem to shed every year." It is extremely painful and the horse will land its foot toe-first to avoid the pain. You probably cannot achieve a heel-first landing if your horse has untreated fungus.

The back half of the frog peels off in deep layers, and the frog is narrow rather than being a wide, healthy triangle. The diseased tissue is light gray to white in color, or black between the peeling layers; healthy frog is medium gray.

"White line disease" is probably a form of fungus. There will be an area where tapping on the hoof wall makes a hollow sound. However, I think most of what people are calling "white line disease" is, instead, due to a flared wall; the stretched white line tissue in a flare does look strange.

|

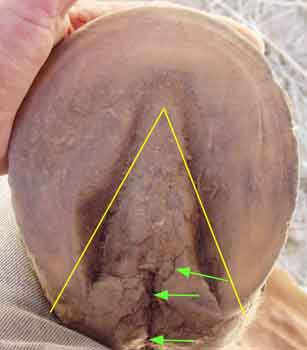

A typical case of frog disease. The back 1/3 of the

frog is flaky, the central sulcus is deep (you could probably put an entire

hoof pick into that crack), and in this case, the fungus has eaten up into

the soft tissue between the heel bulbs.

(This foot also has a side-to-side imbalance. When the wall is trimmed carefully to the edge of the sole on the left side, it should be more level. Also, the concavity is full of sole that has not worn away; just once, we would trim out some of the excess with a hoof knife so the horse can begin to wear its own sole clean.) |

|

The same foot, sole view, again showing the flaky

frog with a deep crack in the central sulcus.

Yellow wedge shows how wide the frog will grow when the fungus infection is gone. The back of the frog will likely grow enough wider to spread the heels 1/2 to 3/4 inch (1 to 2 cm) apart. I moved the point of frog back from its present position, because this horse has a forward-flared toe, which has pulled the point of frog forward from its true position. |

Pat Coleby in Natural Horse Care proposes that all types of fungus infection -- including frog fungus, seedy toe, white line disease, rain rot (a skin problem in rainy areas), and ringworm -- indicate a copper deficiency. Copper-deficient feeds seem to result from the widespread use of nitrogenous fertilizers (rather than compost) on hay and grain fields; the nitrogen suppresses copper availability in the resulting feeds.

Copper deficiency is also associated with runny/drippy eyes, high worm loads, and bot infection.

Pat recommends supplementing 1/2 teaspoon (2 gm.) of copper sulfate daily. Black and chestnut horses may require double that amount as they are more prone to copper deficiency. You should most likely supplement zinc along with copper, as many soils are deficient in both. If you supplement too much of one, it suppresses the other.

An alternative, or a maintenance dose, is to provide free-choice kelp meal (without added urea) in a rain-protected feeder or under a roof. (Other seaweeds would work if you live near an unpolluted coast and can harvest them yourself.)

Local treatments for fungus

Trim away all "shedding" or peeling frog material with a sharp hoof knife -- sharp so that you can cleanly cut away the diseased part. You may see deep, black cracks; trim till all the black is gone and all remaining frog is open to the air. This will let the treatment get to all infected areas. Your horse may be sore in the heels for a few days, but frog grows back really fast when the fungus finally gets treated.

Many people have reported that a severe case of fungus will improve with about two weeks of treatment, then will stop improving. We are beginning to suspect that frog infections are caused by a combination of several different organisms -- one or more types of yeast (fungus) and one or more types of bacteria (thrush). If your horse's frogs stop improving after a couple of weeks, switch to a completely different treatment (see list below). It may be useful to switch several times.

Clean Trax is a chlorine-related treatment that kills both the fungus and its spores. It is the treatment of choice in difficult cases and where the fungus has invaded the white line higher in the hoof capsule. Clean Trax is expensive and requires a very long soak in a tall boot which is hard to do with horses that don't stand still easily.

Some other treatments that work well and are easier:

1) Borax cleaning powder (a laundry product, such as "20 Mule Team Borax" or "Boraxo"), is available at hardware stores and builders supply stores; overseas at the chemist. Borax works by changing the pH (acidity) of the frog to a more alkaline range so that the fungus is unable to reproduce. I found Borax to be successful, easy to deal with, and inexpensive.

Use 1 Tablespoon borax powder in a bucket with enough water to cover the foot. Add 1 dropper of Calendula tincture, an herb that helps with skin conditions, and soak 15 minutes, 4 to 10 times over several weeks to a month. On the in-between days you can soak a cotton ball with this solution and stuff it into the central sulcus. You can stop soaking when there is obvious new growth in the center of the frog.

2) People in the UK are using Zinc sulphate (sheep foot rot treatment) which can be soaked for a short time daily or even kept in a permanent foot bath that the (sheep, horses) walk through daily both for treatment and prevention.

3) Lysol cleaning solution can be used as a soak.

4) "Pete (Ramey)'s Goo." Mix 50% Neosporin (or generic) triple antibiotic cream with 50% athlete's foot cream (clotrimazole 1%) and apply deep into the central sulcus with a syringe. Use daily until there is new frog growth. I like to put boots on with Pete's Goo for several hours; the boot spreads the Goo over the entire frog and keeps it there for a while.

5) Insert Calendula cream or gel deep into the central sulcus, daily until there is new frog growth.

6) Spray the trimmed frog daily with Usnea tincture. I order this by the quart or half-gallon from www.essentialwholesale.com

7) Two treatments that have been recommended to me are No Thrush, a dry powder, and Thrush Stop, easily applied with a small paintbrush.

Immune system

Another point of view on fungus is that it is a systemic infection (throughout the horse's body -- similar to Candida). Therefore we need to build the horse's deficient immune system; really healthy, unstressed horses may not get frog infections. Try several or all of the following:

-

-- Add half a dropper of Calendula

tincture daily in the horse's dinner, also add to the soaking solution; use

until the bottle is empty. Calendula is an herb that supports healing of

skin tissues; hoof (fingernail) and frog are "skin." Other herbs may be available in

other countries.

-- Give 30,000 units of vitamin A daily for several months. This is approximately the amount in a very large carrot, or in a "flake" of alfalfa (lucerne) hay. For horses with sugar restrictions, you can use vitamin A or Beta-carotene from your health food store instead of carrots. Vitamin A is important in healing skin tissues and for overall immune system health. It's important to supplement with Vitamin A in the winter, or any time the horse is not getting a substantial daily amount of green in its diet (grass, leaves, or hay that is quite green).

-- Dr. Ed Sheaffer, a naturopathic veterinarian, notes that an iodine deficiency is strongly implicated in all fungal infections, including rain rot and fungus in the hoof. As with copper deficiency, provide free-choice kelp meal or other seaweed. Seaweed contains all the trace minerals because it grows in the ocean. Horses tend to eat a lot of it for the first few days to catch up on mineral deficiencies; then they eat much smaller amounts as needed, approximately 1 Tablespoon per horse daily.

-- There are many other herbs that boost the immune system. I recommend you talk with your local herbalist, as herbs vary around the world. With some of them, be careful how long you give them; for example, Echinacea is a strong immune system builder, yet begins to deplete the body if used more than about a week. There are many "weeds" that support the immune system, including common ones like dandelion and plantain. If your horse's pasture is lacking in a variety of weeds, find a weedy spot elsewhere and do some occasional hand grazing there.

-- If there is a toe flare, this contracts the heel, squeezing the frog together, so that the central sulcus becomes a crease where fungus lives easily. Keep the toe well backed-up so that the heels can de-contract.

-- Fungus (yeast) thrives on sugars. If you live in an area where the grasses tend to be high in sugars, see www.safergrass.org for suggestions. Eliminate "sweet feed" (grain with molasses) and if possible, eliminate grains, whose starches are nearly as attractive to fungus as actual sugars. Eliminate treats that contain sugar and flour. Several feed companies are making low-starch feeds for insulin resistant horses; these can also be useful for fungus infected horses.

"NAVICULAR SYNDROME"

The conventional veterinary point-of-view is that "navicular syndrome" is a somewhat mysterious disease process in which the navicular bone is attacked by something. The pain is thought to come from disease in the navicular bone. In fact, the navicular bone has no pain-reporting nerves and cannot feel pain.

Conventional treatment is to make the horse comfortable enough, by using "therapeutic" shoes and eventually by cutting the nerves to the foot, so that he can be ridden "as long as possible." When pain control no longer works, the horse is put down. There is no expectation of actually healing the foot.

The barefoot point-of-view is profoundly more hopeful. "Navicular syndrome" is seen as a simple mechanical problem with a mechanical solution: we trim the foot to the natural (wild horse) shape. The goal is the complete recovery of the foot with a return to true soundness.

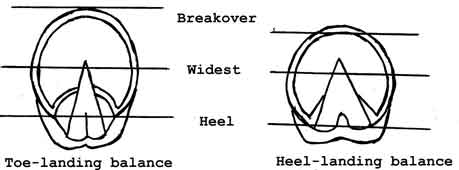

Talking with Gene Ovnicek, there appear to be two reasons for "navicular" pain: 1) painful squeezing of internal tissues due to long, contracted heels and 2) chronic inflammation of the impar ligament, which holds the navicular bone in position, due to incorrect hoof shape that results in the foot landing toe-first. (More discussion on Trim page.)

When the toe, due to improper trim,

has pulled forward from the coffin bone, the hoof tends to land toe-first.

If we back up the toe and shorten the heel, the hoof is able to land heel-first

and does not aggravate the impar ligament.

|

Here is a photo from Gene Ovnicek, showing a hoof that lands toe-first and has been diagnosed as "navicular." The bottom would look like the left drawing, above. |

|

Another hoof, trimmed similar to the one above. Looking from behind, we see very long heels with a narrow frog; the toe has pulled forward, and the hoof is full of chalky, overgrown sole. |

The wild-horse trim, as shown on the Trim page, changes the balance of the hoof so that it can begin to land heel-first. Pain is often reduced substantially after the first wild-horse trim, with full soundness occurring gradually over several months, as the feet land more consistently heel-first, and inflammation in the impar ligament subsides.

HEALTHY HOOVES FOR FOALS

Foals are born with perfect, tiny hooves. If they are given living conditions similar to what a wild horse has, their feet and legs will develop with no problems. But most foals in captivity live in conditions quite different from what their feet actually need.

It appears that the first hour of a foal's life is critical to hoof health. In the wild, the mare moves the foal quickly away from the place of birth, because predators are attracted to the afterbirth and of course to the foal as well. So the soft foal feet, consisting mostly of raggedy frog tissue with a lot of proprioceptive (tells the brain about limb position) nerve endings, get about an hour of movement on hard ground before the foal ever nurses. Gene Ovnicek believes that this hour of movement is a "window of opportunity" which gets the hoof started towards a lifetime of correct shape and function.

In order to develop healthy hooves, foals should not be on soft bedding at all. Instead, from "day one" they should get 10+ miles (15+ km.) of daily movement on hard, uneven ground (not pavement). They should follow along with their mother, who should also be going 10+ miles per day for her own health and hoof care. You can arrange that they move a lot in their 24-hour turnout -- see Jaime Jackson's book Paddock Paradise. If a "track layout" is not possible, riding the mare and ponying the foal is another possibility.

Foal hooves are nearly cylindrical at birth. It takes a lot of concussion on hard ground (which horses are designed for) to spread the hooves out into the shock-absorbing cone shape of the adult horse. In soft footing, and especially in bedding, the feet just sink in without flexing. Some foals soon develop a very contracted foot where the base is actually smaller than the coronet -- the walls are "inside the vertical." (See Photo Gallery 2, #10 a foal and #15 an adult hoof "inside the vertical.") This is extremely difficult to rehabilitate.

Wild foals run with the herd on hard and often rocky ground. Wild horses move 20 miles (30 km.) or more every day, just getting food and water. Foals are "precocious" young, which means they are born able to keep up with the herd (different from other animals' young which must be carried by adults or hidden from predators).

Bone alignment in the leg depends on having sufficient movement on firm terrain. The pasterns are nearly upright at birth. They need lots of movement so that the pastern bones align into the harmonic curve which gives shock absorption in the leg.

The ligaments and tendons in the legs, as well as in the upper body, can only become as strong as the work they do every day. The toughest ligaments and tendons come from plenty of daily movement on hard or rocky ground. A horse raised this way will be able to handle the athletic demands of an equine sport without breaking down.

Dr. Strasser and Gene Ovnicek both note that the "problem" legs that some foals are born with, generally align themselves correctly within 2 weeks, without veterinary intervention, if the foal gets sufficient movement and is not kept on soft footing. A foal at my friend's farm gained good alignment and leg strength in this way within about a week.

Here is a foal's Right Front at about

6 weeks. She runs around in 24 hour turnout, but the ground is soft in

our climate, so her feet don't wear much. The "after" is close to the shape

of her feet at birth, though the feathery frog cover is gone (see photos

below).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here are some feet from a one-week-old

draft horse foal. They are typical even though they are huge.

|

Front foot.

Green arrow points to the remains of feathery tissue that covers the frog at birth. It contains proprioceptive nerve endings, which tell the brain where the limb is in space. A foal needs to begin walking on firm ground right away so that these nerve endings can get foot-to-brain communication working well. This helps the feet develop and ensures the horse will feel connected with its feet. |

|

Hind foot.

Again you can see the remains of the feathery frog tissue around the frog, now crushed by a week's wear and starting to wear off. |

|

Side view of a hind foot.

I have put three lines showing the direction of growth of the hoof wall. No part of the hoof grows straight down -- the entire hoof capsule grows forward. I especially wanted you to see that the heel grows forward too, so that normal heel growth cannot be called "underslung." |

SUGGESTIONS FOR TRIMMING FOALS

Mainly what you need to do is the same as an adult horse -- trim the wall and the heels down to the edge of the sole. In a young foal, the wall is not thick enough for a mustang roll, though you can round it a little with some medium sandpaper.

You have three choices of tools: the soft side of a hoof rasp, a hoof knife (top quality as described on Tools page, and very sharp so it does a good job), and/or a sandpaper block. With the soft side of the rasp, it only takes a few strokes to trim a foal. Trimming with a hoof knife would be similar to trimming a goat's feet, just shave off the wall to the edge of the sole. A sandpaper block is good if you're afraid of trimming too much.

Before you can trim a foal you have to to teach it how to balance on three legs so you have at least a brief time to work. (For a very young one, you may be able to trim briefly while she's lying down.) I would suggest clicker training www.theclickercenter.com because it's very specific and the horse can learn quickly. Make a "tock" sound with the tip of your tongue (different from the "chick-chick" sound that means "go"), as a marker, as she starts to do what you want , and scratch the neck as the immediate reward each time you click. For foals, scratching is better than a food reward.

Alternatively, use "natural horsemanship" techniques. Ask with a light, steady touch, and release your touch, immediately, when the foal even thinks about responding -- it may be just a shift of weight at first; let her relax and think a moment, then ask again. This will quickly build into her understanding and doing what you want. Picking up a foot with your strength will be counterproductive in the long run, especially as she gets heavier and stronger. Much better to let the foal figure out what you're asking and make her own decision to help you. This gets a horse off to a good start for a lifetime of dealing with the human world.

I would do many, very short sessions over several days or weeks. Get the foal comfortable with picking up her feet easily, and then help her learn to balance 3-legged for every foot, before trying to trim at all. Be sure to set her up with the diagonal leg farthest away so she has a good tripod to stand on while you've got the work-foot in your hand. They learn quickly to set up if you show it to them (forward or backwards a step so the diagonal foot is farthest -- this means teaching "move away from pressure" before you teach "pick up foot"). She will soon put the diagonal leg in a good spot when you start to ask for the leg you want. And then only trim a little and let her go.

Always put the foot down before she has to take it, even if you didn't finish what you wanted to do. This way she is always successful in helping you, and gets rewarded (gets her foot back) for doing what you wanted. It shows her you are a reasonable person and a good leader, and she will be more willing to work with you.

Doing TTEAM circles with each leg is another good thing to do (on Trim Prep page and in Linda Tellington-Jones's books). Making tiny circles with the lifted foot helps them relax the muscles in the hip and shoulder -- you will feel when the leg relaxes into your hands. They like how it feels and after several days' practice will start to offer each leg as you come around, "Please do this one, too!" Then you can use TTEAM circles as a "thank-you" when she has let you do some trimming on a foot.

Many foals seem to prefer that you hold the foot high up near their body, rather than partway down to the ground as an adult horse generally prefers. You can use TTEAM circles to gradually show the foal that she can relax her leg, that it's OK for it to be in a lower position.

It is fine, when you get to longer trimming sessions, to offer some hay (at chest height, for balance reasons) so she can nibble and be less impatient with you, if that seems to help. In the beginning, if you're working long enough to need hay, you're working too long.

I encourage you to go ahead and start

asking for feet, and gradually start playing with a sanding block or the

soft side of a hoof rasp. You don't need to do all the feet at once, nor

even a whole foot in one session -- it can be an ongoing game where she

gets scratched every time she figures out what you want, and the session

ends when she makes a nice try, such as holding the foot up for two seconds

when she'd been holding it for one second. No need to "get serious," just

enjoy the teaching -- a foal's feet are important but the trimming is so

minor that you can do it on-the-run.

COLTS STARTING IN WORK

A horse's feet continue to get wider until the horse has reached its full adult weight, at about age 5. The hoof gets broader as the horse gets heavier. The coffin bone reaches its adult size and shape at age 5.

When a young horse is shod, generally at age 3 when training begins, it restricts the growth of the feet. The coffin bone is no longer able to grow into its correct shape, because the "wall of nails" around the edge of the shoe interferes with further widening. Shoes also begin to contract the heels. The coffin bone grows in a narrowed shape, and the heels curve in towards the frog.

I hope that people raising young horses

will decide not to shoe them. The horse that stays barefoot will be more

confident because, as it learns to do its job, it is able to feel the ground

and know where its legs are. A horse raised barefoot is graceful. Its movement

is glorious to behold. I believe that once we begin to see some adult horses,

raised barefoot, we will realize what we've been missing in our athlete

friends.

HOOF DAMAGE FROM CARRYING RIDER'S WEIGHT?

When riding any horse, the guideline is not to ask the horse to carry more than 15% of his weight, though stocky-built ponies seem to be able to carry more than this without difficulty. Wild horses add 20% to their weight each fall, in preparation for winter. Mares in foal carry 15-20% extra weight.

In a barefoot horse, the weight of a rider makes the hoof flex a bit more. The tough yet elastic hoof materials absorb the extra concussion.

If you think about it, it's the shod horse that has more trouble with the rider's weight. In a shod horse, the hoof doesn't flex, therefore the horse loses 70-80% of his shock absorption. Instead, the concussion travels up the leg, putting extra wear-and-tear on the joints.

Horses that have completed the transition

to barefoot have beautiful, tough feet, unlike anything we're used to seeing,

and they carry a rider with no trouble over any type of rough ground.

GMO'S IN HORSE FEEDS

Some basic information about Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO's), also called Genetically Engineered (GE) crops -- to help you think about what you want to feed your horse.

Most GE crops are made by Monsanto, one of the "Big 3" agri-corporations. So far, the GMO's that have been developed are not about improved nutrition or hardiness, as Monsanto would have us believe. The modified plants are only designed to survive huge applications of the pesticide "Roundup," which Monsanto sells; they are called "Roundup Ready."

About half of the soybeans and corn planted in the U.S. are already GE. Other major crops are also engineered. (See www.safe-food.org/-industry/crops.html.) There is no labelling of GE batches of these crops, so they cannot be traced to their farm of origin; therefore most soybeans, corn, and other major feeds that we buy probably contain at least some GE grain.

Seeds of Deception by Jeffrey Smith presents the best information I have found about GE crops. He describes a dozen aspects of GMO's that either have not been tested at all, or Monsanto has lied about. A few of these are:

-

1) There is nothing precise about the

way foreign genes are introduced into an organism. Genetic material is

sprayed into cells in a "shotgun approach" in the laboratory; there is

minimal control of which genes are being inserted, or of where they will

end up in the DNA of the engineered grain. Given the unknown and complex

working of genes during an organism's lifetime, many "side effects" (unplanned

and unexpected effects) can and do occur. By 2004, at least 20 humans,

and probably many livestock, have already had extremely strange, fatal

results from eating them.

2) Contrary to Monsanto's assurances, the engineered genes appear to be easily passed on from the original GMO to other organisms. For example, gut bacteria take in the new genes after a single meal eaten by livestock. There is no way to predict nor to protect ourselves and our animals from unplanned GM mutations of disease organisms.

3) Once GE crops are planted in an area, the pollen (which contains the GE genes) blows into neighboring fields and pollinates them. Farmers who planted GE-free seed end up with a GE harvest that they did not want; and Monsanto has been requiring that these farmers pay a royalty on that harvest, under the copyright laws. A courageous Canadian farmer, Percy Schmeiser, has been fighting Monsanto in the Canadian courts, with many setbacks from big-business-oriented judges.

Dairy farmers have noticed that when they offer both normal and GE corn, their cows will eat the normal corn and leave the GE corn. Only cows given no choice will eventually eat GE corn when they get hungry enough.

As it is difficult to find organically grown animal feeds, this is another reason to change your horse's diet to mostly hay, with a minimal addition of protein (needed by the body for daily maintenance and repair of cells).

It will be good if lots of us start

asking at the feed store for GMO-free or organically grown grains. Some

farmers have already gone back to non-GE crops because of "consumer preference."

We can support and encourage their refusal to plant GE seed.

TRIMMING DONKEYS AND MULES

There are two photos "after trim" in Pete Ramey's book Making Natural Hoof Care Work for You. There are also several pages about donkeys in Jaime Jackson's Horse Owners Guide to Natural Hoof Care, with one photo of a wild donkey foot. Both available from Star Ridge Publishing, www.star-ridge.com, phone 1-870-743-4603.

Here is a webpage with a drawing and photo of a well-trimmed donkey foot: http://home.vicnet.net.au/%7Edonkey/trimmedhoof.htm

As a proponent of the wild-horse trim, I would disagree with their point #6, "The wall and the sole [should be] neatly rasped, level from side to side and from heel to toe." Horses are sore when we rasp the sole; donkeys may not show soreness from a trimmed sole, but I would still hesitate to rasp the hard sole. My preference would be to scrape out any chalky material and trim the wall only to the edge of the sole, as we do with horses.

The donkey and mule foot is similar to the horse, except that the frog is set farther back behind the hoof wall, and the entire hoof is longer and narrower, sometimes even pinched inwards along the quarters. It is this shape because the donkey is a dry-rocky-terrain animal and this shape gives them the best traction on rocks.

The principles of trimming a donkey foot are the same as for a horse. Scrape out all chalky layer of exfoliating sole (there can be a lot if they haven't been trimmed in a while), till you get to the hard sole. Then trim the hoof wall, including heels, down to the edge of the sole.

In my experience you really only need to mustang roll the toe area, but you can experiment with how far to continue the roll around toward the heels, and on rocky ground they will probably round it off themselves -- I live where the ground is soft and that's really difficult for donkey feet. If you or the donkey doesn't put on a mustang roll, the toe very easily starts to flare forward and goes into the curled-up-slipper-toe situation.

Because the foot is small and narrow like a pony foot, it will "look" more upright when trimmed to the edge of the sole. Reason: The coffin bone of all equines is the same height, but spreads out wider in a bigger, heavier animal. So the heel bulbs in a donkey will be about the same actual height as a horse's and this will make the small hoof appear to be more upright overall. Just trim wall length to the edge of the sole and it will be correct.

The bars slope way down into the deep concavity, so trim off everything that is longer than the adjacent sole. If you have shortened the heels a lot, make sure you trim the back part of the bar to be a little below the level of the wall (no ground contact).

If the hoof was very overgrown, the frog may need some cleaning up. Trim any nasty-looking diseased frog, and any loose tatters.

The frog will get in much better condition when the heels are kept short enough, because it has stimulation from the ground. If conditions have been wet, donkeys can get fungus just like a horse, and it's worth soaking with borax (laundry powder in some water) several times over a week or two. Then the frog can grow plump and happy. A happy frog is important because it contains proprioceptive sensors (they tell the brain "where this limb is") that let the donkey know when the foot has touched the ground, which they need for surefootedness on uneven terrain.

In New England, where I lived for a while, the ground is soft and wet but there are miles and miles of old stone walls -- the "stock fences" of white settlers before wire was invented. I recommended to several donkey owners that they move their electric fence to the outside of the stone wall, so the donks would have something rocky to climb on. If you don't have stone walls, I'm sure donkeys living on soft ground would enjoy a dump-truck load of rocks and/or gravel in their paddock and it would be great for their feet.

The main challenge in trimming donkeys is not the trim itself, but that many of them don't get enough groundwork to be good about picking up their feet. A little time reviewing some "natural horsemanship" with a donkey will go a long way in gaining his helpfulness and make trimming much easier.

Donkeys are very survival-oriented, with a slightly different "flavor" than horses. If they have had a more or less wild or non-working lifestyle, it's a really big deal for them to give up their feet to you -- the feet are their means of escape. Be respectful that they aren't being pigheaded, it truly is scary for them. Show them clearly and politely that "I mean you no harm, I won't hurry you, and I make sense." Especially, give an immediate release of pressure in your request signal, every time they even think about doing what you asked. They are fast learners when you are clear and precise with your releases.

I haven't lived around donkeys but have

been told that once they decide you are benign, sensible, and truthful,

they really like having a "good leader" and will be very helpful for you.

"CLUB FOOT"

What I understand about club feet from talking with farrier Gene Ovnicek:

There are two kinds of club foot:

- 1) A human-made kind where either

the foal wasn't trimmed at all, or wasn't trimmed early enough to keep

the heels short; or in an adult horse the farrier lets the heels get a

little longer on one foot at every trim without noticing, and when he finally

notices the difference, he says "That's just the way that foot is, it's

a club foot and I can't change it."

We can recognize a human-made club foot because the heels are often contracted, and especially, the bars are generally curved and "laid-over" somewhat onto the sole.

This kind can be returned to a normal shape fairly easily by scraping out the accumulation of chalky excess sole in the seat of corn and shortening the heels to the level of the hard sole. With the heels at ground level, one can often see that the toe has flared forward -- this is hard to see when the heel is long. If the toe is forward, back it up with a vertical cut and/or apply a toe rocker (see Trim page). This will allow the hoof capsule to re-shape itself, and the curved bars will straighten by themselves.

2) A "true" club foot becomes long-heeled as a compensation for some kind of injury, often soft-tissue injury in the shoulder. When the range of motion of the leg is restricted by an old injury, apparently the horse's body "prefers" that that leg have an even stride with the other leg, rather than have a perfect hoof, so it grows a longer heel to make that leg reach as far as the un-injured one -- even though the long-heeled foot is potentially less sound.

This "compensation" type of club foot has a strong heel structure with upright, flat bars -- the heel looks like a fortress. The sole thickens in the heel to a level that works for the horse.

This kind of club foot should be respected for the job it's doing for the horse. Don't try to shorten it, other than keeping up with normal growth (wall getting longer than the sole in the seat of corn).

It can be worthwhile to get some regular massage sessions for the horse, with extra attention put on the shoulder area of the club-footed leg. If the soft-tissue injury is able to loosen up and give better range-of-motion, then the foot will "tell you" to shorten the heel, by gradually retracting the sole, and you can follow the sole down to wherever the horse now needs the heel length to be.

If a club foot has some flare (often near the bottom), take it off with a vertical cut.